Ruins of Ancient Star Cluster Found at Milky Way’s Edge

January 5, 2022

Gemini Observatory helps reveal that a stream of old stars at the fringes of our galaxy is a shredded star cluster

A primordial stellar stream discovered in the outer reaches of the Milky Way has a lower proportion of heavy elements than any known stellar system in our galaxy. Observations with the Gemini Observatory, a Program of NSF NOIRLab, showed that the stars in this stream were torn from an ancient star cluster and are relics from the early days of the Milky Way, which could provide insights into the formation of the first stars.

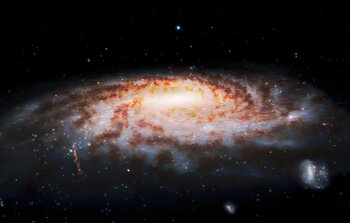

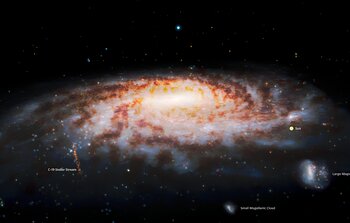

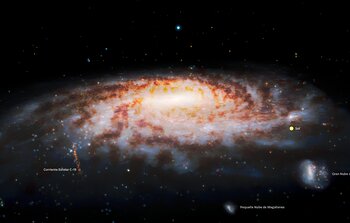

An international team of researchers including members from Europe, Canada, and Russia has discovered a unique stream of stars orbiting the Milky Way [1]. Called C-19, the stellar stream is south of the spiral of the Milky Way, and its orbit extends about 20,000 light-years from the Galactic Center at its closest approach and roughly 90,000 light-years at its farthest. The stellar stream stretches across an impressive expanse of the night sky — roughly 30 times the width of the full Moon — although it isn’t visible to the naked eye.

Using the Gemini North telescope — located in Hawai‘i as part of the international Gemini Observatory, a Program of NSF’s NOIRLab — and the GRACES instrument [2] the team realized that C-19 is a remnant of a globular cluster. In addition, the stars in the stream possess a uniquely low proportion of heavy elements, or as astronomers phrase it, low “metallicity” [3]. Globular clusters were previously thought to have metallicities no lower than 0.2%, but C-19 has an unprecedentedly low metallicity of less than 0.05% — lower than has ever been observed for a stellar system in the Milky Way or its surroundings.

The discovery that a low-metallicity stream originated from a globular cluster has implications for the formation of stars, star clusters, and galaxies in the early Universe. The very existence of the stream proves that globular clusters and the first building blocks of the Milky Way must have been able to form in low-metal environments, before successive generations of stars supplied the Universe with heavier elements [4].

“It was not known if globular clusters with so few heavy elements exist — some theories even hypothesized they couldn’t form at all,” commented Nicolas Martin of the Strasbourg Astronomical Observatory, who is the lead author of the Nature paper reporting this discovery. “Other theories suggest that they would all have long-since disappeared, which makes this a key discovery for our understanding of how stars form in the early Universe.”

Members of the team originally spotted C-19 in data from the Gaia mission [5] using an algorithm they designed specifically to detect stellar streams. The stars in C-19 were also identified by the Pristine survey — a search for the lowest-metallicity stars in and around the Milky Way using the Canada-France-Hawaii Telescope in Hawai‘i — as being interesting enough to merit follow-up observations. To identify the origin of C-19’s constituent stars, astronomers needed the detailed spectra from GRACES [6]. The team also gathered data using a spectrograph mounted on the Gran Telescopio Canarias on La Palma in the Canary Islands.

“GRACES provided the critical clues that C-19 is a disrupted globular cluster and not the more common disrupted dwarf galaxy,” explained Kim Venn of the University of Victoria, the lead investigator for the GRACES observations [7]. “We already knew that this was a very metal-poor stream, but identifying it as a globular cluster required the precision metallicities and detailed chemical abundances only available with high-resolution spectra.”

The Gemini observations suggest that the cluster must have formed from very early generations of stars, making C-19 a remarkable relic from the time when the very first groups of stars were being formed. Consequently, this discovery improves our understanding of the formation of stars and star clusters that arose shortly after the Big Bang and provides a close-to-home natural laboratory in which to study the oldest structures in galaxies.

“This artifact from ancient times opens a direct and unique window onto the early epochs of star formation in the Universe,” concluded co-investigator Julio Navarro of the University of Victoria. “While astronomers can look at the most distant galaxies to study the early Universe, we now know that it is possible to study the oldest structures in our own galaxy as fossils from those ancient times.”

“This international collaboration reveals startling new insight into the structure, evolution, and formation of our galaxy,” added Martin Still, Gemini Program Director at the National Science Foundation. “The Gemini observatories continue to demonstrate key advances in the understanding of our night sky, concerning the cosmic ecosystem and our own place in the Universe.”

More Information

This research was presented in the paper “A stellar stream remnant of a globular cluster below the metallicity floor” in the journal Nature.

The team is composed of Nicolas F. Martin (Strasbourg Astronomical Observatory), Kim A. Venn (University of Victoria), David S. Aguado (University of Cambridge, Instituto de Astrofísica de Canarias, and Universitá degli Studi di Firenze), Else Starkenburg (University of Groningen), Jonay I. González Hernández (Instituto de Astrofísica de Canarias and Universidad de La Laguna), Rodrigo A. Ibata (Université de Strasbourg), Piercarlo Bonifacio (Observatoire de Paris), Elisabetta Caffau (Observatoire de Paris), Federico Sestito (University of Victoria), Anke Arentsen (Université de Strasbourg), Carlos Allende Prieto (Instituto de Astrofísica de Canarias and Universidad de La Laguna), Raymond G. Carlberg (University of Toronto), Sebastien Fabbro (University of Victoria and NRC Herzberg Astronomy & Astrophysics), Morgan Fouesneau (Max-Planck-Institut für Astronomie), Vanessa Hill (Université Côte d’Azur), Pascale Jablonka (École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne and Observatoire de Paris), Georges Kordopatis (Université Côte d’Azur), Carmela Lardo (Università degli Studi di Bologna), Khyati Malhan (Stockholm University), Lyudmila I. Mashonkina (Russian Academy of Sciences), Alan W. McConnachie (NRC Herzberg Astronomy & Astrophysics), Julio F. Navarro (University of Victoria), Rubén Sánchez Janssen (UK Astronomy Technology Centre), Guillaume F. Thomas (Instituto de Astrofısica de Canarias and Universidad de La Laguna), Zhen Yuan (Université de Strasbourg), and Alessio Mucciarelli (Università degli Studi di Bologna and INAF–Osservatorio di Astrofisica e Scienza dello Spazio di Bologna).

NSF NOIRLab(National Optical-Infrared Astronomy Research Laboratory), the US center for ground-based optical-infrared astronomy, operates the International Gemini Observatory(a facility of NSF, NRC–Canada, ANID–Chile, MCTIC–Brazil, MINCyT–Argentina, and KASI–Republic of Korea), Kitt Peak National Observatory (KPNO), Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory (CTIO), the Community Science and Data Center (CSDC), and Vera C. Rubin Observatory(operated in cooperation with the Department of Energy’s SLACNational Accelerator Laboratory). It is managed by the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy (AURA) under a cooperative agreement with NSF and is headquartered in Tucson, Arizona. The astronomical community is honored to have the opportunity to conduct astronomical research on Iolkam Du’ag (Kitt Peak) in Arizona, on Maunakea in Hawai‘i, and on Cerro Tololo and Cerro Pachón in Chile. We recognize and acknowledge the very significant cultural role and reverence that these sites have to the Tohono O'odham Nation, to the Native Hawaiian community, and to the local communities in Chile, respectively.

Links

Contacts

Kim Venn

kvenn@uvic.ca

+1 250 415 5135

Professor, Physics & Astronomy

University of Victoria

Vanessa Thomas

vanessa.thomas@noirlab.edu

+1 520 318 8132

Public Information Officer

NSF NOIRLab